With translations from the Spanish by Leo Boix

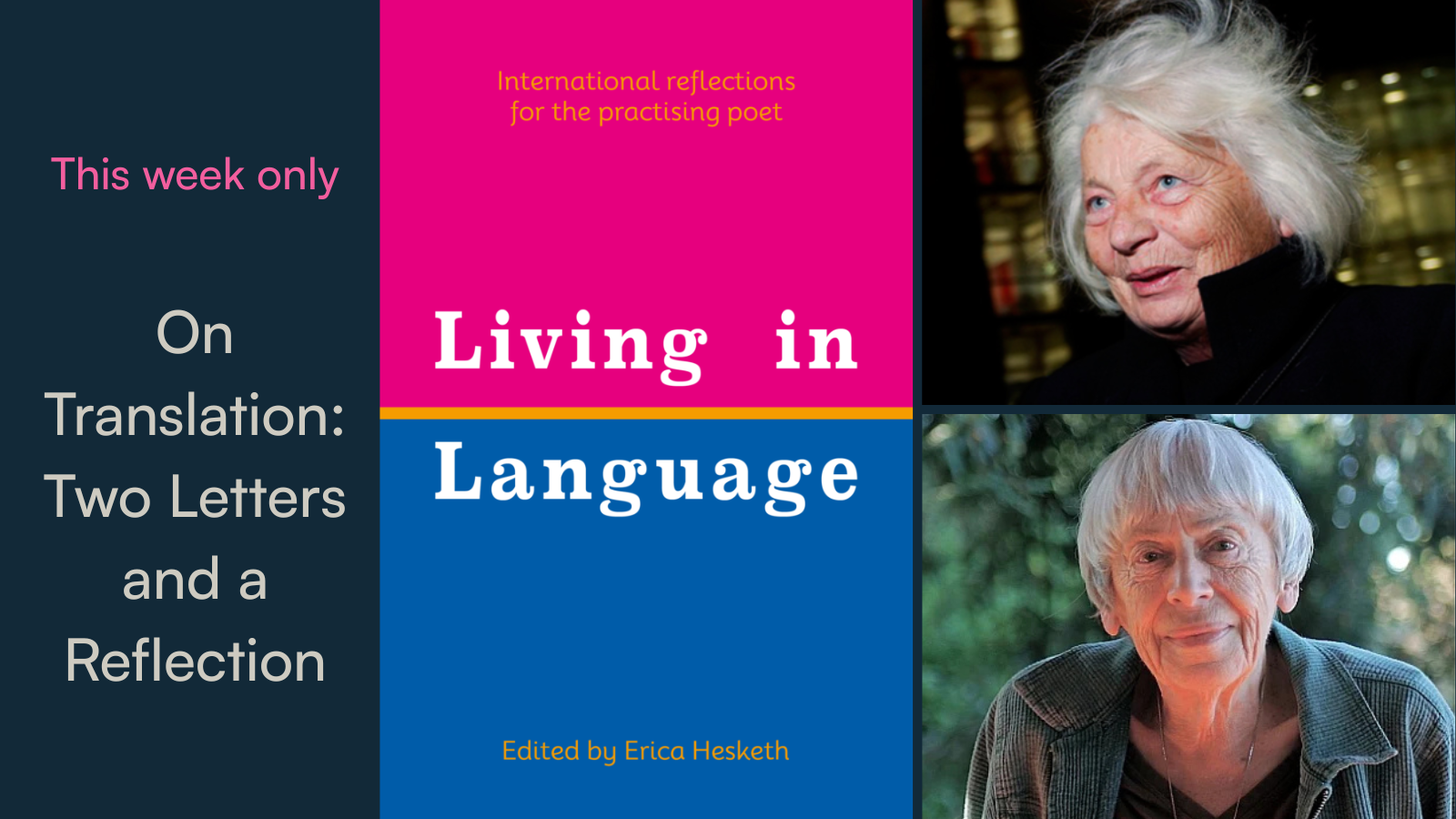

A LETTER FROM URSULA K LE GUIN

She wrote me letters about my books, funny, crazy, fascinating letters I had to answer. We wrote back and forth. She made my letters crazy too, and I loved writing her. That was fun, that was easy. All words. I love words.

Then all of a sudden she writes, I’m coming to see you. I’m arriving from Florida on the plane. Now I was scared. Now it wasn’t a game of words any more, now it was a person, some crazy poet from Argentina flying into my life, disarranging me. What do I do with her, what do I say to her, what does she want from me? I’m in the middle of a book and I don’t want to stop for a stranger. She thinks she’s coming to see the dream-hero she’s made me into in her mind, and she’ll find a middle-aged housewife who’s afraid of people, shy, selfish, no kind of hero, and she’ll be disappointed, I’ll let her down, oh, why is she coming?

I knew her the moment I saw her among the people coming off the plane, tawny, a small puma woman, beautiful, with a beautiful smile full of diffidence and pain.

We talked, we read our poems to each other. She laughed easily, she cried easily, she read her poetry in her lovely husky voice. We have met twice again since then, laughed and cried and read poetry. We always write, but our letters get lost because the Argentinian Post Office does something with them other than delivering them, and so half the time we don’t know how things are going with the other one. Usually it goes along pretty much the same here with me, but in Argentina things have been bad, there have been times I worried about her, not hearing, not knowing. We send registered letters saying Dear One are you all right?

I learned French well long ago, Italian not so well. All the little Spanish I know I taught myself from books. Late in life I discovered that I could stumble along through Spanish translations of my own novels. So I tried Diana’s compatriot Jorge Luís Borges, with the dictionary at hand, and soon cried Aha! How clever I am! I can read Spanish! But then I tried other writers, and found I was not so clever. Is it because Borges spoke English before Spanish that his writing is so lucid to us, or is it the great purity of his diction? I don’t know. I do know that I still don’t know Spanish, that Neruda is very hard for me to read and Gabriela Mistral is very very hard for me to read, that I cannot speak the language, and that I have no right at all to translate from it.

But I began to play with Diana’s poems, just to see if I could understand them, for my own pleasure. She had been translating some of my poems, and I longed to be able at least to read hers. Though all her later books were far beyond me, their allusive usage and syntactic subtlety demanding a true, intimate knowledge of her Argentinian Spanish, I found to my great joy that the first two were accessible if I was methodical about looking up the words. I got a better Spanish-English dictionary and set to making English versions.

Translating is a way of making a foreign-language poem part of yourself. Spanish isn’t the only language I don’t know that I have translated from. This sounds foolish or boastful. I’m not Ezra Pound. What I mean is, I read the extant translations, and sometimes none of them seems quite right, so I begin to collate and change them, referring back to the original to pick up any words, repetitions, echoes, resonances that I can. I have done this with Lao Tzu for years (and have finally begun to do it methodically.) I have done it with Rilke. The Macintyre translation of the Duino Elegies is the only one I can stand; the others all seem more interference than transference. Rilke’s French poems I could and did genuinely translate, but I don’t know German at all, and so with several of the Elegies I have used Macintyre as a guide to making, not a translation, but my own private Rilke. I think this is a legitimate exercise. So, since I knew Spanish better than I do German, and a whole lot better than I do Ancient Chinese, I thought maybe I could get at Diana’s poems in the same way, even without any translation as a guide.

I fell in love with them at once, and went on scribbling translations, every line a discovery, a shock of surprise and satisfaction. Nothing so restores the miraculousness of language as reading real poetry in a language you don’t really know. It’s like being two years old again. The words blaze out, they live lives of their own, mysterious, amazing.

I confessed to Diana what I was doing, and began to send her my scribbles. She sent them back with suggestions and explanations. She set my verbs straight when I thought hear meant sit, or got the right verb in the wrong person, tense, and number. It’s not so much fun, maybe, being chewed up by the two-year-old. But she was joyously patient, and I blundered joyously on.

I would never have shown my versions to anyone but her, let alone print them, if she had not worked on them with me (always through the maddening unreliable mail), correcting, suggesting, and finally approving. These translations – hers of me, mine of her – are collaborations in the truest sense of the word. We worked together.

Crucero Ecuatorial is a very young book, and I love the young Diana who wrote it, long before I knew her – this little lioness going lithe and fearless along the roads of the Americas, looking at old Nazis and young fishermen and Peruvian prizefighters, laughing, sleeping in ancient sacred places, seeing the ‘cracked, bare, quick, flat’ feet of the fieldworkers, seeing everything tenderly and calmly with her golden eyes.

Tributo del Mudo comes from troubled times and was written, though only a couple of years later, by a maturer woman. The delicate Chinese echoes of its first pieces lead to increasingly rich, powerful, complex work, which I have found, as I worked on it over and over, to be inexhaustibly satisfying.

Translating is an excellent test of a poem. Sometimes they wear thin as you rub and polish and scrape and adjust your version. None of the later poems in Tributo have worn thin; they have only grown in nuance and resonance as I grow able to go deeper into them. The political terror of the years when they were written is touched on only by the lightest allusions in the second part, but like a drop of red dye those few lines colour and darken the whole book. The passion and strangeness of the dream poems in the third part leads on to the radiant intensity of the love poems and the earthy-transcendent splendour of the final and my favorite, ‘Isla’.

Gracias, mi puma de oro, por el regalo de tu poesía y de tu corazón.

– Tu osita vieja

A LETTER FROM DIANA BELLESSI

My dear, it is a sweet October morning, a sleepy Sunday morning on the still, silent streets. I go for a walk, and my steps lead me to the green, first the Bótanico and then the ‘forest’; that’s what we call these parks: Palermo’s woods. When I left the island and anchored in the city, I got as close to those trees as I could, but now it’s been months since I’ve been here. Every day I go out to watch the trees around my house. I see the first greenery emerging, delicate filigree, almost invisible, and their magical, extraordinary growth, in wreaths of leaves whose variety never ceases to amaze me. Let me name them in my language: fresnos (ash trees), arces (maples), plátanos (plane trees), paraísos (paradises); they are the ones that abound in the streets, and suddenly a (tilo) lime tree, a Judea tree, the aura of a sauce (willow). I have walked these weeks under the inebriation of paradises in bloom, stopped in front of the unique rose of the lapacho trees, and there will still come the blue jacarandas of November when the avenues look like a spilt sea, and then the tipas with their yellow glow.

My steps lead me to the Forest, and already there, as at other times, I cry. With inexpressible happiness. Without understanding why I’m moving away from here. Everything I’ve done in my life has been to get away from it, to return to it; the green. Whilst sitting in the teahouse, drinking the golden green with rice, two giant cats lurk on the short artificial hill of the Japanese garden: one black and the other white, perfect, jumping as if in a dream.

My only One: you were not your characters for me; you were the whole Forest. The first letter I sent you in October, fifteen years ago, when I was still living on the island, was more than a letter: a little box thrown into the air across the continent to the address of a small publishing house in California, Capra, where you had published Wild Angels, a book I brought back with me from a trip. It all started with poetry, you see. I’ll never finish thanking whoever passed it on to you. The little box bore the velvety, dark gold buds that hold the leaves of the plane trees; when they burst and fall gently the little leaves are released into the air. They have a musky, intense smell. They were the jewels that I sent you from the Paraná. A note said, ‘What are you doing to me?’ You answered me immediately with another little box containing a small branch from the Oregon desert, also intensely perfumed.

The almost wordless, pure materiality of the world we both love. But to think that it all started through your words. I’ve read everything you’ve ever written, did you know that? And I still long for your originals. No, you were never your characters. You were the Forest, and I, your characters. Simultaneously, you were a person who wrote those marvellous books, who understood me in such a way, who still knows. You had found your female reader. In my mind, I imbued you with all wisdom and all adventure. And I still believe you possess it.

Today, you are also my friend, my big sister of the North and also my ‘Twin inside the Dream’. I knew that I had the unconscious strength of the Fool: you were creating distant worlds, and I was travelling to them, mind and body, to touch them. You were writing extraordinary stories, while I could barely put into words places and stories I had been to in person, to capture something faint in the vast hiatus of the poem. The silence was interrupted by a sliver of language. To name what? The Forest, and to return to it. The Forest which you unfold luxuriously before my eyes when you narrate, and which escapes with its mysterious touch in your poems – above all those I love most. That’s how I began to translate you: to enter there.

Was it all words to begin with? Perhaps. Then I forced our meeting, and it wasn’t miserable; it was beautiful. We became complete people. We became responsible for our love, and there was room for Charles, Elizabeth, Caroline, Theo, the cats, your house, and the Forest next to your home. And the ranch in the Napa Valley where you translated Crucero, your brothers, your mother, and your father. I cried listening to Ishi’s voice in the museum in Berkeley. My friend, it has been verbal, and we do not know what resonates of the rivers of the mind and heart in the words.

I will tell you now what I think about translating poetry when, as in our case, we choose the one who speaks to us to make her speak. It becomes, perhaps, the closest experience to the poem’s writing; it is carried out in a slow process of self-absorption and silence, weighed simultaneously by the sonorous mass of a song, of a speech originating in a language other than the mother tongue.

Channelling through one’s own emotion the thoughts and feelings of a foreign voice.

The poet recognises something in her writing when, in saying ‘I’, she feels she is uttering a voice that is both close and, at the same time, distant. She feels she is translating into herself something that seems to come from far away in time. If the poem appears first as a rhythm and only later in its own way unfolds meanings, translation is an effort of alterity. The alterity of the body breathing the music of another language and in the strict particularity of a voice that speaks it.

A double effort founded, no doubt, on love and the aspects that allow the translator to identify with various things. An echo, not a replicant, as in the myth of Narcissus, but sustained by the possibilities and mysteries of the mother tongue in which the translator rewrites it. To feel the text with the alert body at the same time of its significance, so that it unfolds in a language where it was not conceived, something – which is always something else – of that rose full of meaning that the original offers. Perhaps that is why the translation of poetry is more ‘intuitive’ and less derivative and logical than other translation tasks. Finally, it is always a meditation on one’s own tongue and language itself since, if translating is to disarticulate the original, questioning the security of the meanings surrounding us, it is also related to our own language, as Walter Benjamin and Paul de Man put it. Poetry as a genre performs this act of doubt, even in its original language, in the most radicalised way. What, then, is its translation? Feelings of betrayal and, at the same time, the joy of reconstruction. Simultaneous mimicry and rupture, in other words, an almost impossible gesture. A gesture matured in a long previous coexistence, in an intimacy of souls where it’s all about the written word, that sonorous carnality which perches on silence, that sequence of signs on the empty space.

I salute the beauty that your poems still possess in Spanish, a generous and wise language, nourished by the countries of the South that speak it with its tributaries of Quechua, Aymara, Mapudungun, Guaraní…, with their Italian resonances here in Argentina. I salute them, and I know how many echoes have been lost in translation, echoes full of meaning that every word and every syntactic or sonorous game brings in its original language. I know of the impossible gesture that all translation is, and even more of the poem that pretends to be almost pure materiality, the Forest itself. There I lose you, where I go to look for you. Yet our book has been our greatest gesture of mutual love which rests in a gesture of alterity, of letting be – in words – the other woman.

May the waters of the Klamath and the Paraná shelter our words, and may they turn them into the murmur of water from the same continent, without oppression or tutelage, like the twins they are, sailing towards the great river.

– Lovingly, your puma

A REFLECTION BY DIANA BELLESSI

Today, Saturday, the 29th of April 2023, my young friend Cecilia Paccazochi came to visit. She joyfully entered my house, bringing a book of Ursula K Le Guin’s complete poems. She had opened it randomly on the bus on page 325, where she found the poem ‘Hexagram 49’*, which goes like this:

How could I not love her? She

wants what cannot be

owned, or known, or gone;

the way she seeks to find

is the other one; the me

she hunts does not exist, her

‘baby, mother, friend, sister,’

purer, stronger than ever I

or woman was, her ‘interlocutor

in the secret rivers of the mind.’

She transforms all to forest.

She shames the owning, knowing,

gaining of an end, she shines

incandescent, without compromise.

All that was and will be lost

is golden in the puma’s eyes.

The fire in the secret river.

How could I not love her?

The collection to which it belongs, Sixty Odd**, was published a year after The Twins, The Dream. Later, Cecilia and I found the copy of the book which Ursula had sent me, complete with the dedication: ‘To my golden puma, with love and gratitude, from her old bear, Ursula.’ On page 15, where the poem appears, there is the following message in her handwriting: ‘You know that this is your poem.’ ‘Hexagram 49’ is in dialogue with our letters, and rereading it surprised me as much as the photo in her film The Worlds of Ursula K Le Guin. Rediscovering that poem made me reread our letters as if they were written yesterday.

It would be simpler if I were not a lesbian to talk about this love story for what it was. ‘How could I not love her?’ says Ursula in her poem, and I could repeat it. We were two women who loved each other without touching each other. ‘It has been by word of mouth, and we do not know what resounds from the rivers of the mind and heart in the words,’ I wrote to her in my letter. As Ursula says in her poem, we were interlocutors in the secret rivers of the mind.

I was inspired to meet her because of Wild Angels, the 1974 collection of her early poems, but immediately after, I read her prose: The Lost Hand of Darkness and later, The Word for World is Forest. The impact of the latter book whilst I was living in the bush on the Paraná River made me write to Capra Press, Ursula’s publisher. This is when I began to translate her, to enter the Forest that she was unfolding before my reader’s eyes. This is also how I discovered the books of her mother Theodora Kroeber, and how I got closer to all that she loved. When I translated her poetry, I did it through the echoes of her narrative and from her voice, imitating the crows of Oregon. I was not her translator; I was her twin, with a 30-year age difference.

The translator, if they are able to choose who will make them speak – and this is the paradox which disrupts the image of them as merely a ventriloquist, a passive, obedient hand, in the colonial mode – if they are able to choose, and yet not force their own will on the text – a challenge faced by some male translators of poems written by women – then they have the possibility to construct a region that is truly expansive and on which they may insist their whole life.

Translating is also an extension of a prior gesture: reading. And it is the collection of readings accumulated throughout the poet’s life that constitutes that lineage in permanent transformation. In those roots and in that trail which accompanies us, which contextualises us, I can pay homage and, at the same time, make visible a debt of love and knowledge to the American female poets who have occupied my days in reading and translation. Among them, you, my beloved little bear, until forever,

– Your golden puma

*Ursula K. Le Guin, Collected poems, Library of America (2023).

**Sixty Odd, Shambhala Publications (1999).