When I attended my first workshop at Wardrobe Place in March 2017, little did I know that the Poetry Translation Centre would have such a great impact on my life. What prompted that first visit was a curiosity I’d long felt over translation as a discipline and, I must confess, the fact that Wardrobe Place was a five-minute walk from my office.

My mother tongue is Greek, but I write poetry in English. Before finding out about the PTC, I’d tried my hand at translating Greek poets such as Cavafy and Yiannis Ritsos but found the results rather stiff, lifeless. Greek is not among the languages the PTC translates from, but I hoped attending the workshops would help me pick a skill or two in translation.

I won’t forget the warm welcome I received from Erica and Bern during my first visit to the PTC, not to mention the offer of fig rolls – a soft spot of mine. And it was great to meet poet/facilitator Clare Pollard, whose Ovid’s Heroines, a translation of the Roman poet’s Heroides, had greatly impressed me. What was a revelation to me that evening – we translated Jordanian poet Amjad Nasser’s ‘Stone’ – was our use of a literal, or ‘bridge’ translation, brought in by Atef Alshaer, to approach Nasser’s powerful prose poem.

We went through ‘Stone’ line by line, questioning almost every word in Atef’s already excellent translation. We tried to stay as close as possible to the spirit of the original, while identifying which words and phrases could benefit from an alternative to Atef’s choice. Passion built up in the room as we debated whether ‘wounds’ or ‘shot-marks’ best described the kind of damage humans can cause on a stone. The Arabic word allowed for marks made by other weapons such as arrows, but we agreed that our final choice, ‘bullet-holes’, evoked the strongest image. When Clare read out our final translation, it sounded so smooth, so beautiful, it felt almost magic.

After that first session I was hooked. Not only has the PTC offered me the opportunity to practice my translating skills, it’s also broadened my awareness of the world of poetry beyond the UK and the US. I’ll never forget the puzzling humour and subtle sadness of Cuban poet Legna Rodríguez Iglesia’s ‘Ms Trolley Recalls Countries’ and ‘White Trash’ – the latter generating one of the PTC’s most memorable lines – Fuck you, train – the first of many we’ve thought would look great on a t-shirt. The opening lines in Iraqi poet Kadhem Khanjar’s unflinching ‘We are the Iraqis’ – The American soldiers in the helicopter throw / leaflets with inked arms onto our sleeping women / on the rooftops – haunts me. Every single line in Roy Hasan’s gutsy ‘In the land Ashkenaz’ leaves me amazed. And I still feel the anger I felt when we translated Adelaide Ivanova’s ‘for laura’, a fiercely political, unbearably sad elegy that confronts the violence committed against trans and gay bodies. I wrote a response poem to ‘for laura’ and return to its PTC translation all the time. When I visited Porto recently – the tiny Livraria Poetria is a gem of a bookshop, by the way – getting hold of a physical copy of O Martelo, Ivánova’s collection that includes the poem, meant a lot to me.

The PTC has helped me become a braver poet and translator. Without it I may never have tried to translate my beloved Andreas Aggelákis – he’s a Greek gay poet who, his life cut short by AIDS in 1991 at the age of 50, speaks to me more than any other Greek poet – let alone submit my translations of Aggelákis’ poems to Modern Poetry in Translation. Working on them through an initial, literal translation I produced was a crucial part of my process. The poems’ inclusion in MPT’s recent LGBTQ issue, ‘The House of Thirst’, was one of the proudest moments of my life. I have the PTC to thank for this. I’m now working on more translations of Aggelákis, which I hope to put together in a collection. It’d be wonderful to share more of his incredible poetry with the world.

In a way, the journey I began with my first visit to the PTC came full circle when a month ago I co-hosted with Clare a workshop on translating LGBTQ poetry at the Poetry in Aldeburgh festival. This time we had an hour, rather than the PTC’s usual two, to translate ‘[ 9. escort: the trick ]’, a compact, profound, tongue-in-cheek poem by the Greek poet Vassilis Amanatidis. I provided the literal translation. Poetry in Aldeburgh provided the wine. Yes, there was a whiteboard and red marker pens.

Among our 15-strong group of curious and intelligent poets – a tough crowd! – debate over almost every word was intense. My literal opening line, He is the technique of illusion, was changed to the more graceful, mysterious His technique is illusion. Being in the bridge translator’s seat was illuminating. Question after question was thrown at me, keeping my mind in overdrive, while testing my memory of my mother tongue, which can be patchy after 20 years in the UK. I may have started sweating. It was important to me that every single person in the workshop contributed in one way or another to the creation of the final translation. I hated the thought of anyone leaving disappointed. There is nothing more wonderful than to look at a line or word in a collaborative translation and think: ‘I came up with this!’

I’ll never forget how it felt sharing the PTC workshop experience that evening at Aldeburgh. When I finished reading to the group our final version of Amanatidis’ poem, I was very close to crying with happiness. Translation feels like home now.

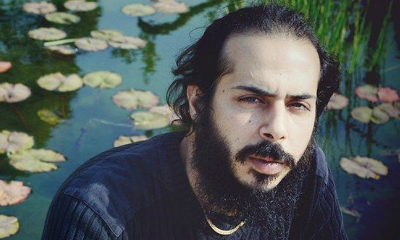

Kostya Tsolákis is a London-based Greek poet, journalist and translator. His poems have appeared in Envoi, Strix, The Fenland Reed and Brittle Star, his translations in MPT. He is co-editor of harana poetry, a new online magazine for poets writing in English as a second or parallel language.