Imagine living in a society where poetry was considered to be the most important art form. Where a poet could easily fill a football stadium. Where a poet’s death was the top news story for days. Where dictators would ply poets with gifts and flattery in invariably futile attempts to get them on side. Where scientists and economists and government ministers would find it unthinkable not to read poetry every day. Where everyone could recite the national poets by heart.

And yet, odd as it may seem to many British people, these societies exist. In fact, your next-door neighbours may hail from just such a place.

I defy you to find a Palestinian who can’t recite one of Mahmoud Darwish’s poems. In August, when this incomparable poet died, the whole of Palestine, and much of the Arabic-speaking world, came to a halt. Stricken with grief, no one could talk about anything else for days.

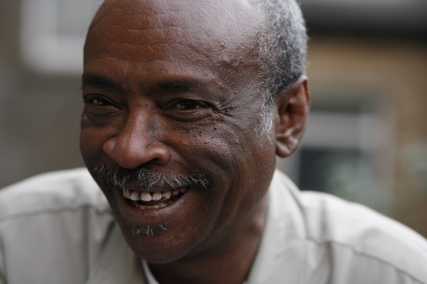

In 1989 when the dictator Omar El-Bashir, seized power in a coup in Sudan, the young Sudanese poet, Al-Saddiq Al-Raddi, decided to fight back with the only weapon at his disposal: his poetry. In the face of a complete news blackout, Saddiq and his friends gave impromptu poetry readings – in the streets, in schools, in cinemas – drawing crowds of thousands of people simply by word of mouth.

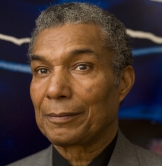

Despots have never taken kindly to poets. The great Somali poet, Maxamed Xaashi Dhamac “Gaarriye” was threatened with a death sentence by the Somali ruler, Siad Barre. Barre was rattled by a chain of poems inaugurated by Gaarriye that protested against the kind of divisive, tribal-based society on which Barre’s rule depended. Barre was so threatened by the power of Gaarriye’s words that he insisted anyone caught selling a cassette of the poems should be executed.

Both Al-Raddi and Gaarriye were part of the first World Poet’s Tour arranged by the Poetry Translation Centre (PTC) in 2005. Travelling with them, I was astonished to see the fervour with which they were greeted. Countless Sudanese and Somalis just wanted to be seen with them, to shake their hand. It felt a bit like being on tour with Bob Dylan in 1965.

Now they’re back the UK for this year’s tour, alongside four other leading international poets, Corsino Fortes (from Cape Verde), Kajal Ahmad (from Kurdistan), Noshi Gillani (from Pakistan) and Farzaneh Khojandi (from Tajikistan).

We’re bringing them here not only for the obvious pleasure they give, but also because I hope that translating their poetry into English will go some way to injecting something of their energy into British verse. Poetry in this country is our favourite minority artform, largely greeted with bafflement, often with dismay. And yet we live alongside people for whom poetry is a central, essential passion. My hope is that by attempting to make their poems at home in our language, we can also translate a little of their enthusiasm.

Poetry thrives through translation. Where would we be if Chaucer hadn’t turned The Romance of the Rose into English? Or if Wyatt and Sydney hadn’t translated Petrarch, thus introducing that quintessential English verse-form, the sonnet, into our language? If Ezra Pound hadn’t become fascinated by Chinese poetry – leading to his masterwork, Cathay, in 1915 – modernism would have taken a very different turn.

The list goes on. Every significant innovation in English poetry occurs as a result of poets engaging with translation, either by translating themselves, like Dryden, or by falling under its influence – most famously like Keats first gazing into Chapman’s Homer.

I’ve been translating poems since I went to Palestine in 1996, and realised I could put my skills as a poet at the disposal of other poets. Working closely with Palestinian poets and translators, I revised and rewrote until something emerged that remained true to the original poem and sounded to me like a poem in English. The PTC, which I founded in 2004 has been using the same method ever since. The poets on this year’s tour have been translated by collaborations between experts in language and culture, and leading poets in the UK, including Sean O’Brien, Jo Shapcott, Lavinia Greenlaw, Mimi Khalvati and WN Herbert.

We’ll be travelling to events in 11 cities across the country. Maybe, for a short time, we can see what it feels like to live in a society that truly values poetry.

Read Sarah Maguire’s article on Guardian Online