The act of editing can be a kind of reliving: a chance to recover, explore, and – crucially – to reconceive the past. When that past is a repository of many good memories, it can also be a great joy, and so it was when Erica Hesketh, CEO of the Poetry Translation Centre, asked me to work again with Said Jama Hussein on assembling an anthology of ten years and more of translation – done both under the auspices of the Poetry Translation Centre, and those of Kayd Somali Arts and Culture – in order to celebrate ten years of the Somali Week Festival.

When she did so, I realised that it must also be ten years since the PTC’s founder, Sarah Maguire, came and spoke to me after a presentation I did at SOAS with the Chinese poet Yang Lian, on some of the translations we’d been working on from contemporary Chinese poetry. The subject was poet-to-poet translation, or how writers like myself, with no grasp of Chinese, could translate through close dialogue with a Chinese poet. With her was Martin Orwin, the foremost expert on Somali poetry at that institution, and a great advocate of the work of one of the giants of modern Somali poetry, Maxamed Xaashi Dhamac ‘Gaarriye’.

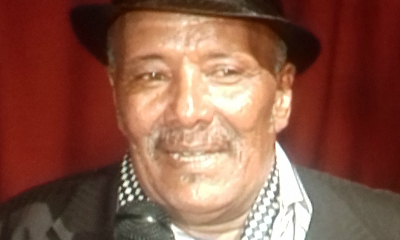

Sarah approached me to enquire if I’d be interested in working in a similar way to translate Gaarriye, and I remember that she appealed to my sense of a challenge: Somalis, she told me, are a people obsessed with poetry, so you have to get it right; Somali is the language that makes Arabic look easy, she added. And just to make it irresistible, Gaarriye is loved by his audience in a way with which no British poet could possibly compete. No pressure there, then.

Within a year I was being swept along in a convoy of poets led by Gaarriye around a triangle between Hargeysa, Boorama, and Berbera, to read the translations Martin and I had laboriously assembled, phrase by phrase and line by line, to the hundreds who gathered wherever Gaarriye performed one of his mesmerising, sharp, witty, transformative readings.

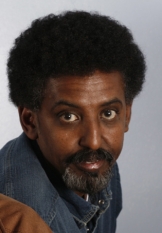

In the sense that it transformed and developed my own writing, I felt then, and up to his shocking, premature death, almost on the edge of Gaarriye’s ‘xer’, that group of younger writers and academics which included many of the names of the up-and-coming generation of poets, including Xasan Daahir Ismaaciil ‘Weedhsame’, whose important poem ‘Galiilyo’ (‘Catastrophe’) Martin subsequently translated with such aplomb with Daljit Nagra.

That began an obsession – with the poets, poetry, language and culture of Somali – that has persisted to this day, and this was what I continually revisited as Said and I worked with Edward Doegar and Erica on assembling the eighteen poets and twenty-five poems of So At One With You.

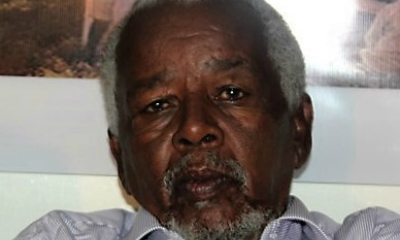

I remember another first encounter, this time with the tight circle of friends – writers, scholars, thinkers – who gathered around the greatest of Somali poets, Maxamed Ibraahin Warsame ‘Hadraawi’, while we discussed how we might work on his dauntingly long, imaginative, various, and daring poems. We were ostensibly talking process and pragmatics, but this was also an interview, to check me out for the role of translating a legendary figure. Through translation (for my Somali was still non-existent), Hadraawi gently explained the pivotal public role the poet must play in relation to an audience that clings to his or her every word – how, almost as a historic necessity, someone must occupy this role responsibly, with humility, but fearlessly, as a voice of conscience as well as a transformative imagination.

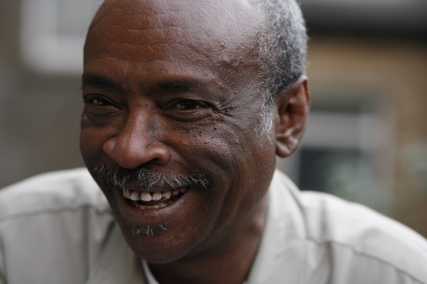

Again, I scraped past the audition, and found myself in another exciting creative unit – ‘Hadraawi team’ as I thought of it, after seeing the phrase painted on a wall in Hargeysa – working from the literals provided by Maxamed Xasan ‘Alto’ through a word-by-word creative dialogue with Said, meeting weekly in the café of a Whitechapel hotel, and assembling the hundreds of lines of the masterpiece ‘Sirta Nolosha’ ‘(Life’s Essence’), or ‘Bulsho’ (‘Society’), the poem from which we drew the phrase “so at one with you” which gave our anthology its title.

And that has been what the editing process has felt like to me, a reassembly of those translation teams, as Said and Martin and I consulted with Ed on matters of ordering, or with Jama Musse Jama on issues of presentation of the Somali text. And the whole process has also been an act of approaching a society of those many other poets and translators whose work is represented in So At One With You, including Sarah herself, now sadly gone, and Clare Pollard, whose marvellous work with Asha Lul Mohamud Yusuf in The Sea-Migrations I watched with great excitement as it appeared over the last five years.

Similarly, as we looked to rounding out and bringing the book up to date, it was a great pleasure to be part, briefly, of another new team of translators with Said, Ed, and Erica, as Will Harris and Anna Selby worked on recent poems by Maxamed Muxumed Cabdi ‘Haykal’ and Amran Maxamed Axmed. As with the moment we received Weedhsame’s fine essay on his sense of cultural inheritance, it was an experience which brought home the particular relevance to this anthology of the social contract we enter into both when we translate and when we edit.

The best of Somali poetry binds together poet, poem and audience, as Hadraawi explained, and as Gaarriye understood profoundly, in an unwritten social contract. Everything – from its unique metrics to its sense of deep moral responsibility and keen sense of what is just, from its care for Somali culture in its historical, political, and ecological setting, to the matter of celebrating, preserving, and exploring the Somali language itself – must be understood in this sense. And an anthology of the best poetry, as I hope So At One With You is, is similarly bound by this contract.

To read and re-read this work, to order, consider, and reconsider its fine detail, to try and get at the bigger picture through others’ essays, and by collaborating on introduction, title, and blurb, by speculating on cover image, and considering the book’s reception by readers both familiar and new to the poetry it celebrates, has to been to relive many glad meetings, and to reflect on some sad losses. It has been a reminder that poetry’s task, intensified by translation and editing, is to bring us closer to that larger sense of life we encounter again and again in these poems, just as I encountered it over that delightful, difficult decade. As Hadraawi put it:

Let these few lines be as striking

as the stripes on an oryx,

as visible and as lovely –

I simply place them in plain view.

So At One With You is now Available to buy from the PTC online shop.