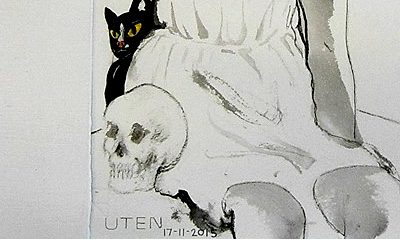

Contemporary poet Uten Mahamid has a niche but growing following in Thailand. He is a northerner from Phayao province, but his sensibility is hardly pastoral. Uten is a highly visual writer, and it’s no surprise, given that he is also an artist (represented by Angkrit Gallery in Chiang Rai, should you happen to find yourself in the very north of Thailand). He has said that in his poetry, as well as his artwork, he likes to create images that tell stories via single shots, and, from what I have seen, that has often meant close-ups, rather than sprawling panoramas. Common motifs in his work include: cats, at once cute and foreboding; the body, often broken down into individual parts that are anthropomorphized; and the penis, as the vehicle for masturbation and urination (both of which are given a painterly quality).

During the workshop, we were able to work our way through two of Uten’s poems that put a couple of his main motifs on display. We translated a three-line poem about the thrill of owning a pet cat (I won’t spoil the plot!) and a longer piece entitled Finger ♥s Blade, involving the wedding between a finger and a knife. I was really pleased by how the workshop participants, guided by our poet-in-charge Clare Pollard, got their hands dirty with these poems. A favorite moment: For Finger ♥s Blade, a PTC regular suggested the word “spilt” (instead of “fell”), which followed the word “split” in the same line. I think Uten would be proud of us for not missing the chance for a good anagram. After all, this is a poet who dabbles in lipograms.

Clare said she would have guessed from the literal translations that the poet was a woman because Finger ♥s Blade made her think of The Cut . I, on the other hand, had read the bleeding finger as a male image, with the blood grouped together with the other bodily fluids alluded to above that recur in his body of work more generally. Interestingly, the group debated whether the finger or the blade was the bride or the groom in the poem.

Uten has written an abundance of three-line poems, a relatively new form of Thai free verse likened to haikus. These poems have no formal requirements except the line count (which Uten has still reduced to two sometimes). While Thai has a flowery and repetitive aspect to it, the language can also be extremely pithy—Thai doesn’t have articles and subjects and prepositions can often be left out, for example—and it is this latter quality that three-line poems trade on and that Uten uses to great effect. For my part, I’d love to come back to PTC and workshop some more of his three-liners alongside more traditional fixed-form Thai poetry, which rhyme internally and play to the lushness of the language.

Drawing by Uten Mahamid